What’s So Hard About Psychological Safety, Anyway?

You don’t have to be a C-Level leader to wonder what challenges present themselves when you dig into the topic of psychological safety. Leaders at all levels and all over the world are struggling with this concept. How do you embed psychological safety into the daily activities of teams?

Read on as I share the results of a case study that twists, turns, and uncovers some surprising secrets that get in the way of fostering psychological safety. The case study is based on a psychological safety survey conducted with a group of senior leaders at a mid-size supplement company. Based on this research, I have learned many leaders are confused by the term psychological safety, so let’s quickly define it.

What is Psychological Safety?

Amy Edmondson defines a psychologically safe environment as one where people will not be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns, or making mistakes [1].

As humans, it is part of our nature to worry about the repercussions associated with speaking up, and challenging or disagreeing with others. We could be labeled as negative, ignored, excluded, or even fired from our job. At the beginning of each psychological safety workshop (via an online zoom chat vote) I ask each participant if, sometime within the last week, they can say ‘yes’ to one or more of the following questions [2]:

- Have you ever felt excluded in a work setting?

- Have you ever remained silent when you knew the answer to a problem?

- Have you ever been afraid to ask a question?

- Have you ever had someone steal credit for something you did?

- Have you ever been ignored in a discussion?

The results are always unanimous. Every participant indicates they have felt excluded, and unsafe, at least once in the last week, in their current job. These results show that feeling unsafe is pervasive. At the same time, most leaders would say they have a desire to foster a work environment where it feels safe to speak up and challenge the status quo.

They also know that when you do challenge the status quo, the team becomes more innovative and creative [3]. Therefore, embedding psychological safety across a company is an important initiative. This is where the challenge begins.

The Biggest Challenge: The Paradoxical Pressure of Leadership

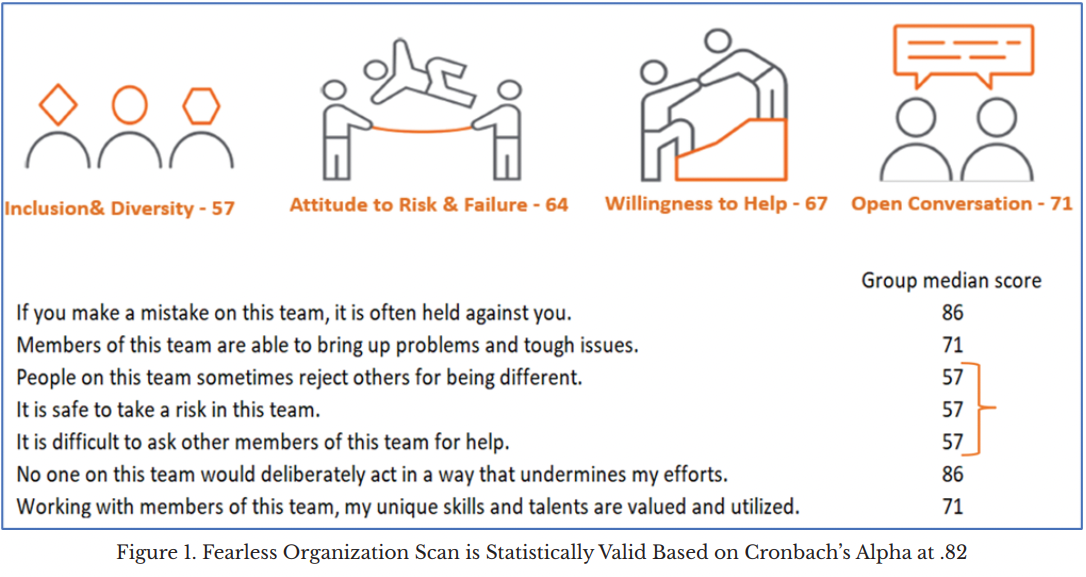

So why is creating psychological safety harder than it seems? A Q1 2022 psychological safety survey based on Amy Edmonson’s Fearless Organization Scan (FOS) provided some insightful answers. The survey consisted of seven questions sorted into four dimensions (shown in parentheses) [4]:

- If you make a mistake in this team, it is often held against you. (Attitude-Risk & Failure)

- Members of this team are able to bring up tough issues. (Open Conversations)

- People in this team sometimes reject others for being different. (Inclusion & Diversity)

- It is safe to take a risk on this team. (Attitude-Risk & Failure)

- It is difficult to ask other members of this team for help. (Willingness to Help)

- No one in this team would deliberately act in a way that undermines my efforts. (Willingness to Help)

- Working with members of this team, my unique skills and talents are valued and utilized. (Willingness to Help)

This survey was completed by an executive team from an anonymous company which included the Chief Executive Officer (CEO), Chief Operating Officer (COO), Chief HR Officer (CHRO), and a mix of seven other leaders from sales, marketing, quality, IT, and manufacturing. The team took the survey with the following goals:

- To gain insight into the current state of psychological safety within the senior team.

- To explore opportunities for improvement based on the survey results in one or more of the four dimensions.

Below is the summary of results with the median score, by dimension and by question.

Each dimension has a span of scores that include a low, mid, and high range. The larger the span, the greater the difference between scores and perspectives within the team. Of the four dimensions, the one with the largest span between the lowest and the highest score was Inclusion and Diversity. This could mean several things but generally indicates challenges in accepting people who differ from the (unwritten) norm or the privileged group.

The survey was anonymous, and based on the range of scores, it appears people approached the survey honestly.

However, when we did a ‘live Zoom’ meeting to review the results, there were attempts to justify the three lowest scores of 57. These justifications included:

- People have not moved on from the past and they don’t trust new management (hence negative feelings from past management issues still linger).

- We have developed in-groups and out-groups because some people are remote and not connected to people at HQ (out of sight out of mind).

- We struggle to ask others for help because everyone is too busy themselves and “People don’t understand my job”.

- Some people are friends outside of work, which creates a bond for them and excludes others.

During the debriefing session, the leadership team came up with the following next steps to address the three lowest areas:

- Hosting a forum—listen to struggles with past management issues (develop awareness).

- Prioritize work—sort work to focus on the top three strategies (be less busy and deliver better quality).

- Cross-training—develop backup staff on roles with a single point of failure and support people asking others for help.

- Host weekly calls—to ensure remote folks feel connected to folks at HQ.

- Promote inclusiveness—openly discuss hobbies outside of work and how to be more inclusive vs feeling excluded.

This was a good start! However, as the practitioner of the survey, I could feel there was something else getting in the way of a safe environment. This is where it starts to twist and turn, as I was aware of individual survey data by question, dimension, and role. Interestingly, the CEO and COO (top executives) had some of the lower scores in the areas mentioned above. However, they did not openly share their feelings and needs with the group.

They listened to others’ perspectives and expressed that the team should let go of the past. The COO appeared to align with the CEO. Overall, they attended to other employees’ needs yet did not address their own. I remained quiet and felt somewhat sad that they did not express their own needs for help and their desire to feel included. Many times, people think the top executives in a company feel psychologically safe and it is everyone else who is struggling. C-level folks feel pressure to appear smart, courageous, optimistic, and confident so that employees will trust in their leadership. This pressure makes it very difficult to be authentic and open about asking for help. It puts them in situations where they distance themselves from friends at work and feel fearful to talk about mistakes from the past. If they appear too open about their needs and stresses, this could cause others to lose confidence in their leadership [5]. However, if the top leaders don’t model inclusiveness and are not willing to ask for help, others will feel similarly. It’s the old saying made manifest: “Do as I say, not as I do”. Sadly, this creates a situation where there is distrust and an underlying feeling that the team environment is unsafe.

To avoid this paradox and address these untold secret needs, leaders need guidance and support. Here are some practical and actionable approaches for senior leaders to address these challenges.

Many times, people think the top executives in a company feel psychologically safe and it is everyone else who is struggling. C-level folks feel pressure to appear smart, courageous, optimistic, and confident so that employees will trust in their leadership. This pressure makes it very difficult to be authentic and open about asking for help.

Addressing the Leadership Challenges:

1. Self-Awareness

Self-awareness is an individual’s tendency to pay attention to their own emotions, attitudes, and behavior in response to specific situations [6]. It’s not clear if the CEO and COO recognized their own needs when we debriefed the results of the FOS survey, or if the dynamics associated with bringing the entire team together to review the results put them on their guard. To foster a safe environment, it’s key that leaders be aware of their needs and can share their needs by “walking the talk”.

How do you build self-awareness [7]:

- Host your own retrospective—write down your plans and goals for your team, then reflect on what is working and why, and what is not working and why. This is your retrospective and allows you to get it out on paper.

- Assess your strengths and development areas—think about what the best part of your day is and why, and what is the most difficult part of your day and why. This helps reflect on specific situations and activities which are more aligned with your strengths, and which are not.

- Get feedback—based on your self-awareness assessment, ask a friend or teammate to provide perspective on your strengths and development areas. This allows you to recalibrate your perspective of self in-line with other, external perspectives. It also allows you to ask others for help in your development areas and provide support in your area of strength. In addition, asking for help models the way for others to also ask for help (win/win).

2. Build Trust

Building upon self-awareness, leaders need to feel a sense of trust within and among their team to foster psychological safety. Trust is the act of building credibility based on two factors [8]:

- Character, which is built on integrity and intention.

- Competency, which is built on capabilities and results.

Trust takes place if people believe that both the character and the competency of their teammates is good, and as a result, they are willing to take a risk and be vulnerable with each other. Trust fosters psychological safety. If you don’t feel you can trust each other, it is difficult to be inclusive, take risks, ask for help, and have open conversations.

3. Get Support

If you, as a senior leader, develop a sense of who you are and your needs (self-awareness) and you have a foundation for trusting one another… what do you do if you still need more support and guidance? As they say, it can be lonely at the top.

Here is how Senior Leaders can get more support:

- Get a Coach—a coach can help leaders see and share perspectives that someone internal to the organization will not see. In addition, coaches are neutral and do not have a position (higher or lower) within the organization. Coaches can be a safe space to share feelings, fears, and areas of concern.

- Get a mentor—potentially a Board member, or past executive with the same role at a different company that could provide insight and be a safe sounding board.

- Join peer support groups—Groups such as YPO, Vistage, local business groups and online meetup forums, can all be a great way to work through an issue.

The results of the FOS psychological safety survey highlight that embedding psychological safety into a team is a complex and challenging endeavor, because everyone at one point or another, including the C-Suite, feels vulnerable and unsafe. That said, building a psychologically safe environment is not impossible! It starts with recognizing your own needs and developing a sense of self-awareness of how you show up in each situation. Then, build trust with one another based on character and competence. Finally, get support through a friend, a coach, a mentor, or a peer group. Psychological safety is the most important thing a team can develop to be successful and productive [9].

This content was originally published in the April, 2023 Edition of Emergence, The Journal of Business Agility. It has been republished here with the permission of the publication.

What is Emergence?

Emergence is the Journal of Business Agility from the Business Agility Institute. Four times a year, they produce a curated selection of exclusive stories by great thinkers and practitioners from around the globe. These stories, research reports, and articles were selected to broaden your horizons and spark your creativity.

References

- Edmondson, Amy C. (2018) The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Clark, Timothy. https://www.leaderfactor.com/post/stage-1-inclusion-safety

- Clark, Timothy (2020) Challenger Safety, from The 4 Stages of Psychological Safety

- Fearless Organization Scan

- Smith, Dena & Grandey, Alicia. The Emotional Labor of Being a Leader

- Benbassat, Jochanan & Baumal, Reuben. Enhancing self-awareness in medical students: an overview of teaching approaches

- Anthony, Tjan. (2015) Ways to Become More Self-Aware

- Covey, Stephen. M. R. (2008). The speed of trust. Simon & Schuster.

- Project Aristotle https://rework.withgoogle.com/print/guides/5721312655835136/